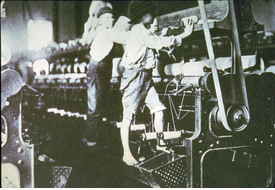

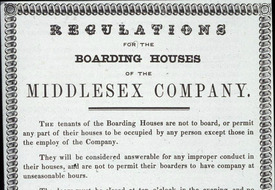

Young 'helpers' in a Georgia cotton mill, 1909

Image ID: 4825

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): Labor, Child labor, Industrialization

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.2 - The the relationship among the rise of industrialization, large-scale rural-to-urban migration, and massive immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe

National Standard(s):

Card Text: Young "helpers" in a Georgia cotton mill. Boys and girls of five or six worked 12 hours a day. 1909.

Citation: Lewis Hine photo. The National Child Labor Committee Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540. LC-DIG-nclc-01581. In Milton Meltzer, Bread and Roses - the Struggle of American Labor 1865-1915, Alfred A. Knopf, 1967, p. 28.

11.2.1

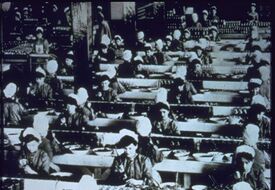

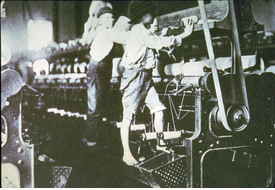

Bottling Room, Heinz Factory, c. 1920

Image ID: 4634

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): Labor, Working Conditions, Industrialization, Women

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.2 - The the relationship among the rise of industrialization, large-scale rural-to-urban migration, and massive immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe

National Standard(s): The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900) , The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Card Text: Bottling Room, Heinz factory. "A hundred girls [sic] pack pickles, one at a time, into spotless bottles with a wooden paddle, giving the pickles a pattern and inserting one red pepper where it will show nicely. There is little dawdling, for the girls get a penny a bottle, and it thus takes 12-1/2 dozen (150) bottles to bring $1.50, considered to be a good day's pay. Twice a week the girls scrub down the room and hands must be kept meticulously clean. A new girl is given a free uniform; thereafter she makes her own from dark-blue white-striped cotton, which she buys at cost from the company stockroom."

Citation: Copyright H.J. Heinz, Co. 600 Grant St., Pittsburgh, PA 15219. All rights reserved. Our thanks to The Heinz Company. In American Heritage, Feb. 1972, p. 37.

11.2.1

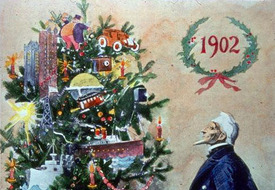

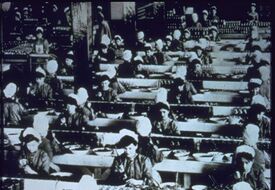

Christmas sketch for Harper's Weekly, 1902

Image ID: 3461

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): Symbols, US Nationalism, Industrialization

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.2 - The the relationship among the rise of industrialization, large-scale rural-to-urban migration, and massive immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe

National Standard(s):

Card Text: W.A. Rogers, Christmas sketch for Harper's Weekly, 1902. It shows Uncle Sam as well-pleased by his growth during the past hundred years. On the Christmas tree are a car, telephone, tall buildings, trolley, ship, oil rig, camera, train, and bags of gold underneath. An American Heritage quotation of Dec. 1976 reads: "We here reproduce Harper's Christmas greeting of 1902, wishing you the best of the season, and in the hope that Americans will sometime again be as proud of what they have wrought."

Citation: Harper's Weekly's Christmas cover, 1902. In American Heritage, Dec. 1976, p. 77.

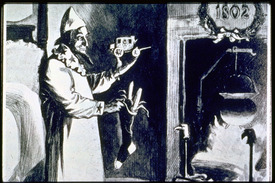

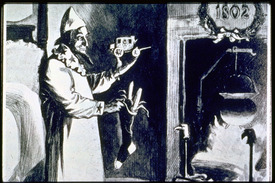

Harper's Uncle Sam celebrates Christmas, 1802

Image ID: 3468

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): Symbols, US Nationalism, Industrialization

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.2 - The the relationship among the rise of industrialization, large-scale rural-to-urban migration, and massive immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe

National Standard(s):

Card Text: Uncle Sam celebrates Christmas, 1802, with a toy carriage and agricultural products in a stocking. Then in 1852 (see companion piece,image #3460,) he is shown with gold from California, a small train and telegraph pole. The first in a series.(#3468, #3460, and #3461)

Citation: Harper's Magazine's Christmas cover, 1902. In American Heritage, Dec. 1976, p. 76.

11.2.6

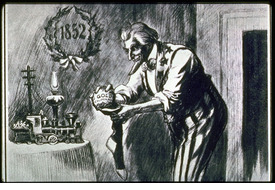

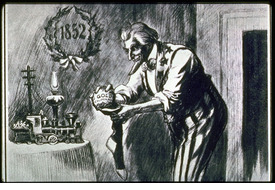

Harper's, Christmas in 1852

Image ID: 3460

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): Symbols, US Nationalism, Industrialization

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.2 - The the relationship among the rise of industrialization, large-scale rural-to-urban migration, and massive immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe

National Standard(s):

Card Text: At Christmas in 1852, Uncle Sam is shown with California gold and a small train and telegraph pole. See the companion piece, SY-U-22.

Citation: Harper's Magazine's Christmas cover, 1902. In American Heritage, Dec. 1976, p. 76.

11.2.6

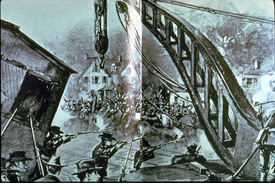

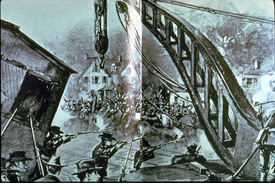

Chicago Pullman strike of 1894

Image ID: 4765

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): Labor, Pullman and Model Towns, Industrialization

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.12 - The transformation of the American economy and the changing social and political conditions…in response to the Industrial Revolution, 8.12 - The transformation of the American economy and the changing social and political conditions…in response to the Industrial Revolution, 11.6 - The Great Depression and how the New Deal changed the role of the federal government

National Standard(s): The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900) , The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Card Text: National Guardsmen firing into an angry mob of demonstrators during the Chicago Pullman strike of 1894. Drawing.

Citation: Harper's Weekly, 1894. In Eds. of American Heritage, An American Heritage Pictorial History of the Presidents of the U.S., Vol. II, 1968, pp. 572-3.

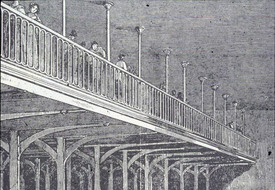

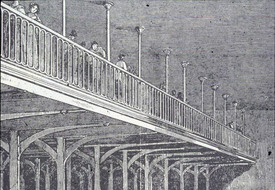

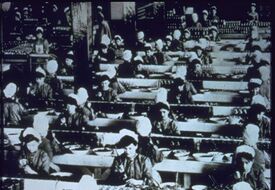

Cotton Mill Interior, England, 1851

Image ID: 8313

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Nineteenth Century, Industrialization, Architecture, British Empire, Business 19th century, Child labor, Cities, Class Structure, Early mills and factories, Emerging industrial city, Environmental History, Gender-Bending, Labor, Market Economy, National Events, Parents, Children, Families, Success 19th century, Sweatshops, Technology, Trade, Urbanization, Women in labor movement, Women's work

Region(s): Europe, United States

CA Standard(s): 8.6 - The divergent paths of the American people from 1800 to the mid-1800s...with emphasis on the Northeast. , 10.3 - The effects of the Industrial Revolution in England, France, Germany, Japan, and the United States. , 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines, 11.2 - The the relationship among the rise of industrialization, large-scale rural-to-urban migration, and massive immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe

National Standard(s): Expansion and Reform (1801-1861), Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877) , An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

Card Text: Mill interior, Dean Mills, The Doubling Room, 1851, detail. Women cotton workers at Dean Mills, a patterned textile factory in Barrow, England, owned by Robert Gardner, who turned it into a model industrial estate with housing and other amenities for workers. As the Industrial Revolution gathered pace, thousands of factories sprang up all over the country. There were no laws relating to the running of factories as there had been no need for them earlier, and then aggressive capitalists fought them to maximize their profits. As a result, dangerous machinery could and frequently did seriously injure and kill workers. To add to these dangers, people were required to work extremely long hours, often through the night. One of the worst features of this new industrial age was the use of child labor. Very young children worked exceedingly long hours and were severely punished for any mistakes. Arriving late for work could lead to a large fine and possibly a beating. Dozing at a machine could result in the accidental loss of a limb.

With time people recognized the danger of these conditions and started to campaign for improvements. Great resistance came from factory owners, who felt reforms would slow their factory production and and make their products more expensive. Many people also disliked government interference in their lives. Many poor parents, too, needed their children to go to work at a young age, as their wages were needed to help feed the family.

Not all factory owners kept their workers in dangerous conditions. Robert Owen, who owned a cotton mill in Lanark, Scotland, built the village of New Lanark for his workers. Here they had access to schools, doctors, and a house for each family who worked in his mills.

In 1833, the British government passed the first of many reform laws regulating working conditions and hours. At first, the government had only limited power to enforce them, but as the century progressed the rules were enforced more strictly. Nonetheless, the hours and working conditions were still inhuman by today’s standards, and no rules were in place to protect adult male workers.

Legislation was passed by the British Parliament to improve working conditions in factories:

1833: Textiles: No child workers under nine years of age; Reduced hours for children 9-13 years; Two hours schooling each day for children; Four

factory inspectors appointed.

1844: Textiles: Children 8-13 years could work only six and one-half hours a day; Reduced hours for women (12); and no night work.

1847: Textiles: Women and children under 18 years of age could not work more than ten hours a day.

1867: All Industries: The previous rules apply to workhouses (poorhouses) if more than five workers are employed.

1901: All Industries: Minimum working age raised to 12 years.

Citation: Image and text: "The 1833 Factory Act," The Illustrated London News, Oct 25, 1851. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/1833-factory-act/. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond TW9 4DU, UNITED KINGDOM. All content is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0, except where otherwise stated. Nov 26, 2022.

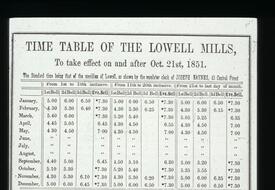

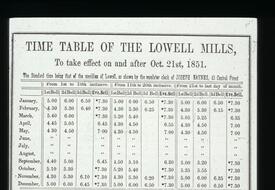

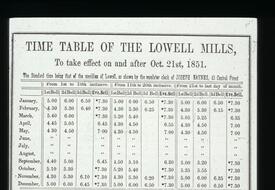

Time Table of the Lowell Mills, 1851

Image ID: 8332

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Nineteenth Century, Lowell, Industrialization

Region(s):

CA Standard(s): 8.12 - The transformation of the American economy and the changing social and political conditions…in response to the Industrial Revolution

National Standard(s):

Card Text: "Time Table of the Lowell Mills" showing hours of labor, Lowell, MA, 1851, “to take effect on and after Oct. 21st, 1851." This timetable does not list all of the bells that the women might have heard throughout the day. The struggle for the ten-hour day, more than any other issue, was the focal point for many workers' organizations in the 1840s. By 1845, factory workers in Lowell were spending an average of 12.5 hours per day performing dreary, exhausting work in onerous conditions. When the time spent going to and from the mills was factored in, the days approached 14.5 hours.

The long hours worsened the already physically- and mentally-debasing factory life. Operatives (workers) wrote that the hours of work were “sufficient to impair health, induce disease, premature old age, and death...to say nothing of the intellectual degeneracy which must necessarily result from the want of mental recreation.” Many were so worn out by their work that they were unable to take advantage of the wealth of educational opportunities offered in Lowell.

The system of long hours was embodied in the factory bells, gates and public clocks that the mills used to regiment the workday. The system of bells established new, industrial work rhythms that synchronized Lowell’s workforce. The bells woke the operatives up, and called them into the mills; they rang at breakfast, called them back into the mills, again at lunch, at closing time, and finally at curfew.

In order to succeed, ten-hour workday initiatives required legislative action, making government and the political process part of reform discussions for the first time. Workers organized several petition campaigns demanding laws that limited the workday. In Lowell, women led these efforts. Although earlier petition efforts found little traction, in 1845 the "Voice of Industry," a workers' newspaper, spearheaded a vigorous campaign that collected over 2,000 signatures (mostly from women). This effort led to the creation of a House of Representatives committee to investigate factory conditions, the first such committee in the United States. The committee was led by William Schouler, an appointment that dismayed many of the activists who had run the campaign. As the editor of a factory-friendly newspaper called the “Lowell Courier,” Schouler was perceived as being biased in favor of the corporations; his newspaper was often described by the Voice as a “political organ of the corporations.”

The committee heard testimony from a number of women who spoke about the dreary work and long hours in the mills. Despite this, it opted not to intervene. Indeed, the committee’s report amounted to a full exoneration of the corporations. A law restricting the workday, the committee wrote, would negatively affect the competitiveness of the mills. It would also affect “the question of wages,” which the committee held should be set by the market, as negotiated between labor and capital. In Lowell, the committee said, “labor is on an equality with capital, and indeed controls it…Labor is intelligent enough to make its own bargains, and look out for its own interests without any interference from us.” The committee concluded by expressing confidence that any abuses in the mills would remedy themselves, through “the progressive improvement in art and science, in a higher appreciation of man's destiny.”

"The Voice" reacted sharply to the report, charging that the political process had been hijacked by the corporations, and accused the committee of distorting the workers’ testimony. When Schouler sought re-election following the release of the report, the Female Labor Reform Association vigorously campaigned against him, likely contributing to his defeat a year later.

Workers in New England had varying attitudes towards the ten hour campaigns. Some believed that they were the first step in a broader reform movement. For others, it was an attempt to simply ease the negative effects of the new economic system, the basic premise of which had already been reluctantly accepted. Still other workers, fearing that a ten-hour system would put a limit on their earnings, refused to lend their support to the movement

Citation: Image: Baker Library, Harvard Business School, Soldiers' Field, Boston, MA 02163. "The Ten Hour Movement." Copyright The Voice of Industry. https:// www.industrialrevolution.org/10-hours-movement. All rights reserved. Sept 7, 2023.

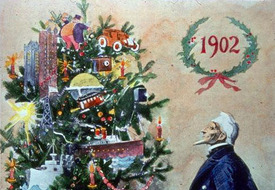

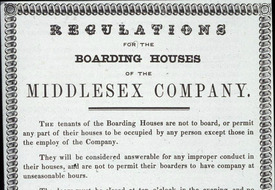

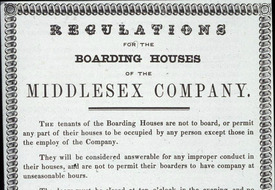

Boardinghouse Regulations, Middlesex Company, Lowell, MA, c.1846

Image ID: 8333

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Nineteenth Century, Lowell, Industrialization, Antebellum Reform, Business 19th century, Child labor, Civil Rights, Class Separation, Corporate Image, Early mills and factories, Early National Period, Emerging industrial city, Environmental History, Family to 1920, Gender-Bending, Immigrants, Individualism, Technology, Institutions and social disorder, Irish, Labor Organizations and Leaders, Market Economy, Mythology, National Politics, Reform, Strikes and Violence, Sweatshops, Technology, Temp to 1870's, Town and city planning, Urbanization, Victorian Culture, Women in labor movement, Women's work, Work and Housing, Working Conditions

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.12 - The transformation of the American economy and the changing social and political conditions…in response to the Industrial Revolution, 5.8 - The colonization, immigration, and settlement patterns of the American people from 1789 to the mid-1800s..., 8.4 - The aspirations and ideals of the people of the new nation, 8.6 - The divergent paths of the American people from 1800 to the mid-1800s...with emphasis on the Northeast.

National Standard(s): Expansion and Reform (1801-1861), An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

Card Text: "Boardinghouse regulations, Middlesex Company," Lowell, MA, c. 1846. Each morning across New England, the factory bells tolled. And six mornings a week, the “Belles of New England” walked through the streets to the mills, trudging, talking, sometimes singing. The Mill Girls became a fixture in America’s brightest pictures of itself.

"O sing me a song of the Factory Girl/So merry and glad and free/ —The bloom on her cheeks, of health it speaks!/ — O a happy creature is she!"

But with time, a different picture emerged. The picture rarely appears in high school history, yet it tells of young women sparking the fight that continues to this day — the fight for a living wage.

The hiring of Mill Girls was driven by both capitalism and compassion. Francis Cabot Lowell had toured England’s “dark satanic mills.” He had seen children working 12-hour days, workers living in hovels, families hungry, desperate, ground into submission. Lowell had a better idea. Why not recruit farm girls? Lodge them in boarding houses? Enrich them with lectures and discussion groups? Hire older women as “keepers” to keep these “factory queens” moral and upright?

When word got out, the plan was widely praised. Poet John Greenleaf Whittier eulogized “Acres of girlhood... The young, the graceful... Who shall count your vocation as otherwise than noble and ennobling?”

At first, the girls agreed. Glad to be free of the farm, they earned enough — $2 a week — to buy clothes, save a little, and send money home. “The thought that I am living on no one is a happy one, indeed,” a New Hampshire girl wrote.

But the Iron Law of wages soon shackled them and the free market's “invisible hand” slapped them down. As more mills and more mill towns increased competition, pay was cut, hours increased. And then there were the mills themselves.

Power looms roared. Windows were nailed shut to keep cotton moist, filling rooms with lint and airborne diseases. Bosses could fire a girl for, as historian Philip Foner wrote, “levity, hysteria, impudence, or simply not being liked.”

The girls responded with spirit and charm. They pinned poetry to looms, put flowers in weaving rooms, tacked math problems on walls. “I defied the machine to make me its slave,” Lucy Larcom wrote. “Its incessant discords could not drown out the music of my thoughts if I would let them fly high enough.”

But as looms were speeded, the girls found themselves stretched as thin as the cotton they spun. Then in May 1824, mill owners in Pawtucket, Rhode Island lengthened the work week. A hundred girls walked out. New England was shocked. This first “turnout” lasted just a week, with the girls settling for only one extra hour in their workday, but it was a start.

In 1828, strikes began in earnest. For the next dozen years, hordes of girls, up to 800 in some towns, walked off the job protesting pay cuts and 12-hour workdays. In Dover, New Hampshire, striking girls formed a half-mile line marching behind a band. In Lowell, the “factory queens” met in secret, then walked out as one, going from mill to mill to gather more strikers. In 1834, America’s first female union, the Factory Girls Association, began collecting dues, forming strike funds, sticking together. Suddenly the pretty picture of pretty mill girls had a stark frame. Factory Girls Association president Sarah Bagley asked, “Is anyone such a fool as to suppose that out of six thousand factory girls in Lowell, sixty would be there if they could help it?” And girls were singing: "Oh! Isn’t it a pity that such a pretty girl as I/Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?"

The fight for a 10-hour day had begun. By the time it was won — in 1874 — the myth of the Mill Girls was fixed in American history. But the girls themselves had gone home. Home where, as one wrote, “I shall not be obliged to rise so early in the morning, nor be dragged about by the factory bell, nor confined in a close noisy room from morning to night, just as though we were so many living machines.”

Economics provided another reason. The growth of mill towns made it impossible to find enough farm girls. By 1850, Irish immigrants were doing the work the girls had pioneered. And America’s Labor Movement -- "the folks that brought you the weekend" -- was taking root, its seeds sown by the Belles of New England.

Citation: Image: University of Massachusetts Lowell, One University Ave, Lowell, MA 01854. https://libguides.uml.edu/c.php?g=536409&p=3671354. Lowell Historical Society, P.O. Box 1826, Lowell, MA 01853. Text: Copyright Bruce Watson, "The Myth of the Mill Girls," The Attic. https://www.theattic.space/ home-page-blogs/2018/8/30/the-myth-of-the-mill-girls. All rights reserved. Aug 28, 2023.

The Pullman Strike, Chicago, 1894

Image ID: 4747

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): Labor, Pullman and Model Towns, Industrialization

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.12 - The transformation of the American economy and the changing social and political conditions…in response to the Industrial Revolution, 11.6 - The Great Depression and how the New Deal changed the role of the federal government

National Standard(s): The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930), The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

Card Text: The Pullman Strike, Chicago, 1894. A fleet of boxcars, set ablaze during the Pullman strike, burns fiercely in a Chicago yard. With rail traffic snarled, supplies dwindled and a meat famine threatened the Midwest.

Citation: In Eds. of Time-Life Books, The Life History of the United States, Vol. 7, 1974, p. 93.