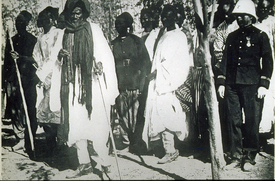

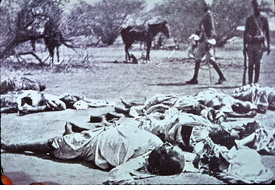

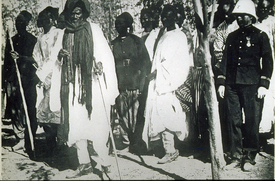

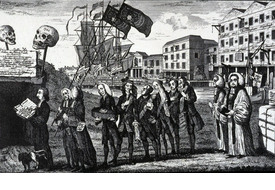

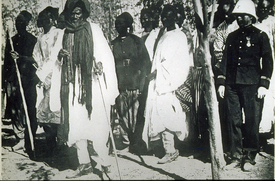

Captured Malinke Leader Samory Touré, West Africa, 1898

Image ID: 13295

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

Card Text: 2-IMG00015

The brilliant Malinke leader Samory Touré (c. 1830-1900) founded the Wassoulou Empire, an Islamic state in West Africa, in 1878. By 1881, Wassoulou extended through Guinea and Mali, from what is now Sierra Leone to northern Côte d'Ivoire. When the French occupied Senegal in 1888 they collided with this resourceful Muslim soldier. Samory successfully resisted French rule in West Africa from 1882 until his capture in 1898; after almost a decade of struggle the French caught him and exiled him to the Congo, where he died. The French then took over upper Guinea and its gold mines.

Citation: René Dazy photo. In "Africa Aeterna: The Pictorial Chronicle of a Continent," text by Paul Marc Henry, trans. by Joel Carmichael, conceived and produced by Georges and Rosamond Bernier, (Lausanne, Switzerland: Sedo SA, 1965) p. 188.

West Africans Examine British Armed Forces Ad, World War II

Image ID: 13469

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): W.W.II, Imperialism, Propaganda, War Posters

Region(s): Africa, Europe

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines, 10.8 - The causes and consequences of World War II

National Standard(s): A Half-Century of Crisis and Achievement, 1900-1945

Card Text: "Together." Young West Africans looking at a World War II advertisement for the armed forces of the British Commonwealth, c. 1940. One man points at the African member of the "team." British war propaganda tried to convey an image of unity among the colonies that was not so apparent in real life. "For King and country. As happened throughout the Empire during the Second World War, men of military age were called up for service in their countries' armed forces. Recruiting propaganda stressed the unity of the British Commonwealth of Nations, a point being reinforced to these young men who are about to join the Royal West African Frontier Force." The RWAFF served as a cadre for the formation of two West African divisions, which fought in Italian Somaliland, Abyssinia (Ethiopia), and Burma. One of several ads produced with similar graphics and the same message.

Citation: Imperial War Museum, Lambeth Rd, London SE1 6HZ UNITED KINGDOM. Online at www.iwm.org.uk. In Trevor Royle, "Winds of Change: The End of Empire in Africa," (John Murray Ltd, 50 Albemarle St, London W1X 4BD UNITED KINGDOM, 1997) Fig. 1, opp. p. 116.

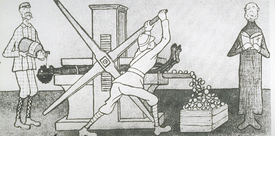

German View of British Imperialism in Africa, 1904

Image ID: 13318

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

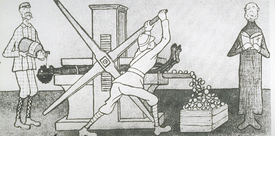

Card Text: 2-IMG00202

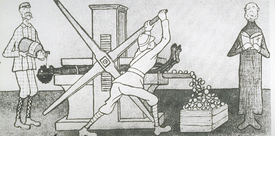

"English Methods of Colonizing Africa," a German view of the British Empire, 19th c. A British imperialist pours alcohol into the mouth of an African, an Anglican priest drugs him with religion, and a soldier squeezes gold (profits) out of him. German, Belgian and French methods were similar.

Citation: Thomas Theodor Heine cartoon, "So kolonisiert der Engländer," Simplicissimus, Special Colonial Number, Munich, GERMANY, 1904; and Oct. 22, 1906. BBC Hulton Picture Library, Unique House, 21-31 Woodfield Rd, London W9 2BA UNITED KINGDOM. Copy in Jan Nederveen Pieterse, "White on Black: Images of Africa and Blacks in Western Popular Culture," (Yale University Press, PO Box 209040, New Haven, CT 06520-9040) 1992. Copyright Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Royal Tropical Institute, Mauritskade 63, 1092 AD Amsterdam, THE NETHERLANDS; and Stichting Cosmic Illusion Productions Foundation, NOVIB, Den Haag, THE NETHERLANDS, 1990. All rights reserved.

Missionaries and South Africans Visit British Parliament, 1835

Image ID: 13653

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

Card Text: 3-IMG00046

An early Christian effort to establish racial harmony in South Africa. "Dr. John Philip led this delegation of missionaries and Christian Africans to a London Parliament Select Committee on Aborigines in 1835-36. Philip campaigned tirelessly for the integration of Africans into the white economy and social system in south Africa, claiming this was the only way to guarantee racial peace there." "Philip was a Scottish missionary and minister in the Cape Colony. He believed that Africans should be converted to Christianity and persuaded to live according to European norms. Yet he stood up for the human rights of Africans under British rule, making him unpopular with the colonial powers. In 1835 Philip traveled to Britain with colleagues and two African converts of the Khoi-Khoi and Xhosa indigenous South African peoples. The evidence this group presented to the House of Commons led the British government to return Xhosa territory taken from them by Britain."

Citation: Museum Africa, 121 Bree St, Newtown, Johannesburg, Gauteng 2001, SOUTH AFRICA. Copy at Hulton Archive, Getty Images, 601 N 34th St, Seattle, WA 98103. Text and photo in "Reader's Digest Illustrated History of South Africa, The Real Story," (Copyright Reader's Digest, 480 Bedford Rd, Pleasantville, NY 10570-2929. Reader's Digest Association of South Africa [Pty] Ltd, 1988) p. 153. All rights reserved. Second text: The Museum of London, 150 London Wall, London EC2Y 5HN UNITED KINGDOM.

Colossus of Rhodes: Cape to Cairo, 1892

Image ID: 13906

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

Card Text: 2-IMG00190

Cecil Rhodes: Cape to Cairo. An English businessman and imperialist in South Africa, Rhodes founded the De Beers diamond company, eventually controlling 90% of the world's diamond production. An ardent believer in British colonialism, he founded the nation of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and was instrumental in assuring British dominance of southern Africa. After becoming prime minister of the Cape Colony in 1890, he used his influence to strengthen British control over southern Africa. His master plan was to establish a Cape-to-Cairo railroad line linking British colonial interests in Africa between Egypt and the Cape. The Boers resisted. After authorizing an unsuccessful invasion of the Boer Republic of Transvaal, Rhodes was removed from office by the British government, but the seeds of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) had been sown. The war began when Britain decided to annex the Boer republics. The fighting was vicious, with the Boers using guerrilla tactics and the British eventually having to use 450,000 troops to achieve victory. In 1910 the British colonies in southern Africa unified as the Union of South Africa, becoming the Republic of South Africa after World War II. This 1892 depiction of Rhodes, diamond magnate and promoter of empire, as "The Rhodes Colossus, Striding from Cape Town to Cairo," became an archetypal image of British imperial power in Africa. In 1887 Rhodes told the House of Assembly in Cape Town that "the native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise. We must adopt a system of despotism in our relations with the barbarians of South Africa." This attitude helps to explain the rise of white supremacy and the decline of his popularity in modern Africa.

Citation: Edward Linley Sambourne cartoon, Punch (London, Dec. 10, 1892). Text: Thomas Caswell, Copyright © 1999-2003 Oswego City School District Regents Exam Prep Center, 120 E 1st St, Oswego, New York, NY 13126. All rights reserved. Our thanks to Mr. Caswell for this concise history.

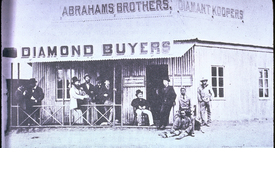

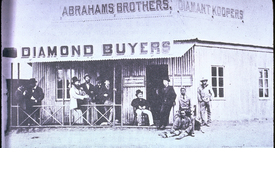

Diamond Merchant, South Africa, 1872

Image ID: 14111

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

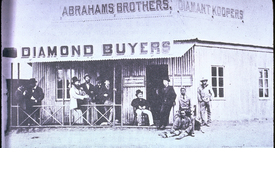

Card Text: 2-IMG00280

Abrahams Brothers, "diamond buyers," Dutoitspan, South Africa, 1872. The 1867 discovery of diamonds in the Cape Colony, now a province of South Africa, radically changed the world's supply of diamonds and its conception of them. As annual world diamond production increased more than ten-fold in the following ten years, a once extremely rare material became more common and accessible to western society with its growing wealth. Science learned that diamonds came from volcanoes, and everyone learned of Cecil John Rhodes, Barney Barnato, Kimberley, and De Beers. Today South Africa maintains its position as a major diamond producer. The story of diamonds in South Africa began in 1866 when 15-year-old Erasmus Jacobs found a transparent stone on his father's farm on the south bank of the Orange River. Over the next 15 years, South Africa yielded more diamonds than India had in over 2,000 years. This great outpouring of diamonds coincided with the depletion of Brazilian deposits and with a great rise in wealth, particularly in the United States, that ensured diamond prices did not fall as they had when Brazil outproduced diamond demand in the 1730s. The first diamond discoveries in South Africa were alluvial. By 1869, diamonds were found far from any stream or river, first in yellow earth, and below in hard rock called blueground, later called kimberlite, after the mining town of Kimberley. In the 1870s and 1880s Kimberley, encompassing the mines that produced 95% of the world's diamonds, was home to great wealth and fierce rivalries, most notably that of Rhodes and Barnato, English immigrants who consolidated early 31-foot-square prospects (claims) into ever larger holdings and then mining companies. In 1888, Rhodes bought out Barnato and merged both holdings into De Beers Consolidated Mines Ltd, a company that is still synonymous with diamonds. Today South Africa is third in production in terms of value and is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future.

Citation: Copyright De Beers Consolidated Mines, PO Box 616, Kimberley, 8300 SOUTH AFRICA. All rights reserved. Text: American Museum of Natural History, 79 St & Central Park West, New York, NY 10024. Online at http://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/diamonds/africa.html. July 10, 2010.

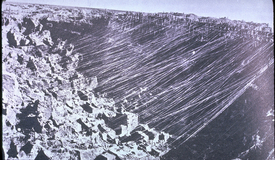

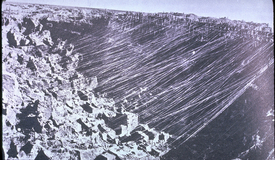

Kimberley Diamond Mines, South Africa, c. 1880

Image ID: 13329

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Unassigned, Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

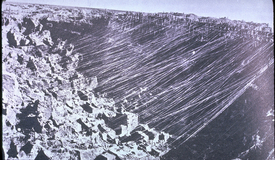

Card Text: 2-IMG00276

Kimberley diamond mines, c. 1880. As the diggings at Kimberley went deeper, each claimant set up his own pulley to extract the diamond-bearing ore. The capital of the Northern Cape Province, South Africa, Kimberley is historically important for its diamond-mining past and siege during the Second Boer War (1899-1902). Capitalists like Cecil Rhodes and the De Beers brothers made their fortunes here. Soon after whites discovered diamonds in South Africa in 1867, the diggings began to penetrate the surface. Chaos followed as individuals and small companies tried to work their claims independently. Gradually, mergers took place, and by the mid-1890s Cecil Rhodes and his associates dominated the mines. "South Side Staging, Kimberley Mine."

Citation: Photo by Aldham & Aldham, Grahamstown, South Africa, c. 1880. Western Cape Archives, Private Bag X9025, Cape Town 8000, SOUTH AFRICA. And Yale University, Sterling Memorial Library, Manuscripts and Archives Collection, PO Box 208240, New Haven, CT 06520-8240. In "Reader's Digest Illustrated History of South Africa, The Real Story," (Copyright Reader's Digest, 480 Bedford Rd, Pleasantville, NY 10570-2929) 1988, p. 170. Reader's Digest Association of South Africa (Pty) Ltd. All rights reserved.

Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia, 1911

Image ID: 13703

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

Card Text: 2-IMG00012

Emperor Menelik of Ethiopia (1889-1913) and King of Shoa (1865-89) unified the Ethiopian highlands, conquered Harrar, and beat the Italians at Adowa in 1896. He negotiated with the French to prevent their expansion on the Somali coast. He managed brilliantly to keep Ethiopia independent at a time of overwhelming European expansion and imperialism in Africa.

Citation: Photo by James William Young of Aden, 1911. In "Africa Aeterna: The Pictorial Chronicle of a Continent," text by Paul Marc Henry, trans. by Joel Carmichael, conceived and produced by Georges and Rosamond Bernier, (Lausanne, Switzerland: Sedo SA, 1965) p. 192.

The Submission of Ashanti King Prempeh, West Africa, 1896

Image ID: 13864

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

Card Text: 2-IMG00205

The racism of European imperialism in Africa: "The submission of King Prempeh: The final act of humiliation, 1896." In Jan. 1896 British authorities, referring to a debt incurred twenty years earlier, invaded Kumasi and surrounded the palace of the last king of the Ashanti Empire, the Asantehene Agyeman Prempeh. Victorious British troops clamored for him to come out of his palace and surrender. The gods had abandoned Prempeh and all hope was gone. Major Baden-Powell described the king's surrender: "When Prempeh emerged, the soldiers commanded the defeated king to grovel before them. It was a blow to the Ashanti pride and prestige such as they had never suffered before. Then came the demand for payment of the indemnity for the war [which the British themselves had caused].... The king could produce about a twentieth part of what had been promised. Accordingly, he was informed that he, together with his mother and chiefs, would now be held as prisoners and deported to the Gold Coast. King Prempeh was marched off to jail. Behind him, soldiers plundered his palace and burned down the sacred Burial-Place of the Kings of Ashanti. This drawing shows the submission of the Asante King Prempeh and the Queen Mother to British officers in 1896.... Virtually the entire continent was forced to submit to superior European force. Asante (Ashanti) had long been one of the most powerful states of West Africa, but after his submission, Prempeh was sent into exile and the British declared Asante a protectorate [colony]. However, the British demand that the Asante surrender their sacred Golden Stool several years later touched off an Asante rebellion in 1900, leading to British armed intervention and annexation by the British crown in 1901."

Citation: The Graphic, (London, 1896). Roger Mansell Collection, Hoover Institution, 434 Galvez Mall, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305. Text: Maj. Robert S.S. Baden-Powell, "The Downfall of Prempeh, A Diary of Life with the Native Levy in Ashanti, 1895-6," (London: Methuen, 1896) Ch. 12. Online at www.pinetreeweb.com/bp-prempeh-12.htm. June 30, 2010.

Ghana's Independence Celebration, West Africa, 1957

Image ID: 13934

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 10.10 - Nation-building in the contemporary world in the Middle East, Africa, Mexico and other parts of Latin America, and China, 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): The 20th Century Since 1945: Promises and Paradoxes

Card Text: 2-IMG00082

The English Duchess of Kent at Ghana's independence celebrations, 1957, West Africa. "First to go." In May 1957 the Gold Coast became the independent nation of Ghana, and the first of many carefully stage-managed independence ceremonies was held. The transfer of power from Britain to each African nation took place at midnight with the Union Jack replaced by the new national flag, usually in front of a member of the British royal family. The Duchess of Kent represented Queen Elizabeth at Ghana's ceremony. Sir Charles Arden-Clarke, in pith helmet, was the British Governor of the Gold Coast colony, 1949-57.

Citation: Copyright holder unknown. In Trevor Royle, "Winds of Change: The End of Empire in Africa," (John Murray Ltd, 50 Albemarle St, London W1X 4BD UNITED KINGDOM) 1996.

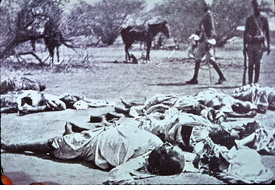

North Africans Resist British Colonialism, Sudan, 1899

Image ID: 14011

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

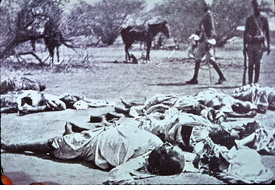

Card Text: 3-IMG00100

North African resistance to British colonialism, Sudan, 1899: After the Battle of Umm Debreika (Umm Diwaykarat), the body of the Khalifa lies in the foreground as colonial African soldiers with rifles look on. Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, known as the Khalifa (1846-99) was a Sudanese ruler and general. He commanded the last of the the Mahdist armies, who were defeated by an Anglo-Egyptian force under Col. Reginald Wingate in 1899 at the Battle of Umm Debreika. This loss ended the short-lived Sudanese empire of the Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. Although devout, intelligent, and an able general and administrator, the Khalifa was unable to overcome tribal dissension to unify the Sudan. Educated as a Muslim preacher and holy man, he became a follower of the Mahdi in 1880. He first fought at the Battle of El Obeid in 1883, where his troops destroyed Col. William Hicks's Anglo-Egyptian army, and he was the principal commander at the siege of Khartoum, 1884-85. At Umm Debreika the Khalifa died fighting on his prayer blanket. The Sudan remained under British control until its independence in 1956.

Citation: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540.

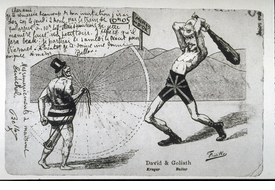

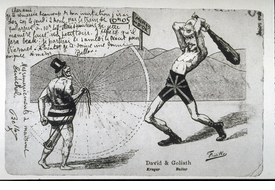

Boer War Postcard, South Africa, c. 1900

Image ID: 14035

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism, War

Region(s): Africa, Europe

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

Card Text: 2-IMG00010

Anglo-Boer War cartoon: A small Paul Kruger, President of the South African Republic, as David about to be bludgeoned by British Gen. Redvers Buller as Goliath. It took over 400,000 British soldiers to defeat the 60,000 Boer fighters during the war in South Africa, 1899-1902. Gold mines in the background. French postcard printed during the war.

Citation: R.B. Fleming & Co. photo. In "Africa Aeterna: The Pictorial Chronicle of a Continent," text by Paul Marc Henry, trans. by Joel Carmichael, conceived and produced by Georges and Rosamond Bernier (Lausanne, Switzerland: Sedo SA, 1965) p. 199.

Zulus Negotiate with British Over Natal, Southern Africa, 1824

Image ID: 14117

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): An Age of Revolutions, 1750-1914

Card Text: 3-IMG00030

King Shaka, who built the powerful Zulu Empire in the 1820s, in a tense negotiation with British Lt. Francis Farewell in Natal, southern Africa, 1824. Shaka offers land to Farewell in return for his support in the Zulu civil war against the Ndwandwe. "The British Dominions Beyond the Seas - No. 1: The Birth of Natal Colony," Richard Caton Woodville painting, 1892.

Citation: Illustrated London News, Dec. 6, 1902. In Robert W. July, "A History of the African People," 3rd ed. (Charles Scribner's Sons, Thomas Gale, 12 Lunar Dr, Woodbridge, CT 06525) 1980, fig. 21. Text: Mary Evans Picture Library Ltd, 59 Tranquil Vale, Blackheath, London SE3 0BS UNITED KINGDOM. Picture No. 10025953.

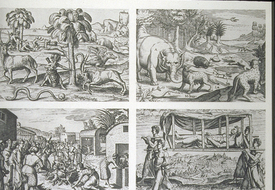

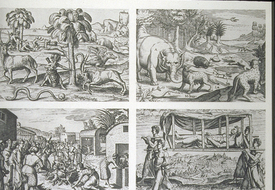

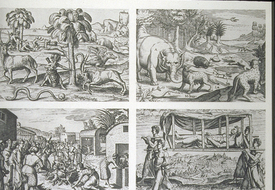

European Impressions of Africa, 1599

Image ID: 14236

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Imperialism

Region(s): Africa

CA Standard(s): 7.11 - political and economic change in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries (the Age of Exploration, the Enlightenment, and the Age of Reason)

National Standard(s): The Emergence of the First Global Age, 1450-1770

Card Text: 2-IMG00024

European impressions of Africa, 1599: 1&2. Unknown animals 3. The King of Congo, converted to Christianity by the Portuguese, orders idols to be burnt 4. Ways of traveling: With no horses, and oxen too large to be harnessed, men bear the burdens 5. The King of Congo asks that missionaries be sent for his people, and the Portuguese immediately comply, adding ornaments, holy pictures and crucifixes 6. How the Guineans hunt and trap (from Vol. 6).

Citation: Theodor de Bry, "Petits Voyages," (Frankfurt, 1599) Vols. 2 & 6. Marc Lavrillier photo. In "Africa Aeterna: The Pictorial Chronicle of a Continent," text by Paul Marc Henry, trans. by Joel Carmichael, conceived and produced by Georges and Rosamond Bernier (Lausanne, Switzerland: Sedo SA, 1965) p. 95.

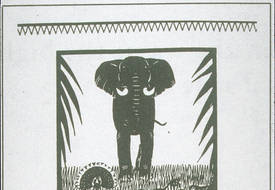

British Ad for Colonial Products from British East Africa, 1926

Image ID: 14246

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): Advertising, Imperialism

Region(s): Africa, Europe

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): A Half-Century of Crisis and Achievement, 1900-1945

Card Text: 2-IMG00189

British ad promoting products and raw materials from British East Africa: Ivory & Apes & Peacocks. New markets for the "British race [sic]." The ad shows the relationship between African raw materials and new markets for European finished goods as causes for European imperialism in Africa. "The land from which, men say, ages ago King Solomon's ships came sailing with their freight of rare and precious things: 'gold and ivory, apes and peacocks.' Today it is British - and of all the tropical domains of the Empire none is richer in promise than this vast territory twenty times the size of England. But today its wealth is of another kind. Coffee from the uplands of Uganda, Tanganyika and, above all, Kenya. Tobacco from Rhodesia and Nyasaland, which also sends us tea. Cotton from Uganda. Sisal from Tanganyika and Kenya. Cloves from Zanzibar. You have a personal interest in the future of East Africa. For as her new industries prosper, her orders for British goods grow larger year by year, and that means more employment and better times for all of us. Drink Empire coffee - smoke Empire tobacco - use Empire binder twine. You'll be helping in one of the greatest colonising ventures to which the British race has ever set its hand. EAST AFRICA sends us COFFEE - TEA - COTTON - MAIZE - SISAL - HIDES AND SKINS - CLOVES - COPRA - OILSEEDS - GUMS - BINDER TWINE."

Citation: Empire Marketing Board, The Times, London, 1926-27. © Copyright Times Newspapers Ltd 2011, 3 Thomas More Square, London E98 1XY UNITED KINGDOM. All rights reserved.

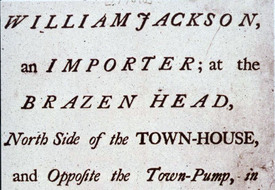

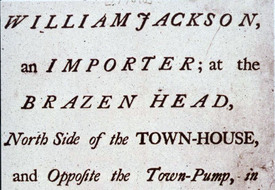

Broadside, Boycott of Merchant who Continued to Stock English Goods, Boston, 1770

Image ID: 7820

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Eighteenth Century, Revolution, American Revolution, British Empire, Business, Civil Rights, Class Structure, Colonial America, Decolonization, Domesticity, Early Ads, Imperialism, Individualism, Technology, Institutions and social disorder, Invention, Labor Organizations and Leaders, Luxury, Middle-Class Culture, National Events, Nativism, Politics & Government, Pre-Industrial Work - Misc., Propaganda, Stores, Strikes and Violence, Symbols, Taxes, Trade, Women in the Revolution, Women's image, Women's organizations, Work and Workers

Region(s): United States, North America

CA Standard(s): 8.1 - Major events preceding the founding of the nation and the development of American constitutional democracy, 5.4 - Political, religious, social, and economic institutions that evolved in the colonial era. , 5.5 - The causes of the American Revolution, 5.6 - The course and consequences of the American Revolution, 5.7 - People and events associated with the development of the U.S. Constitution and it's significance as the foundation of the American republic

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: Broadside urging the American boycott of merchant William Jackson, who continued to stock English goods at his Boston business, MA, 1770. "It is desired that the Sons and Daughters of Liberty, would not buy any one thing of him, for in so doing they will bring disgrace upon themselves, and their Posterity, for ever and ever, AMEN." Like the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767 produced controversy and protest in the American colonies. Many colonists again resented an effort to tax them without representation and thus to deprive them of their liberty. The revenue raised by the Townshend Acts would pay royal governors, taking away the right of colonial legislatures to set or withhold a royal governor’s salary. The Restraining Act, intended to isolate New York without angering the other colonies, had the opposite effect, showing how far beyond the British Constitution some members of Parliament were willing to go.

The Townshend Acts generated a number of protest writings, including “Letters from a Pennsylvania Farmer” by John Dickinson. This influential pamphlet circulated widely in the colonies, arguing that Parliament could not impose either internal taxes, like stamps on goods, or external taxes, like customs duties on imports.

Women were encouraged to boycott British goods, especially tea and linen, and to manufacture their own homespun cloth. Building on the Daughters of Liberty protest of the 1765 Stamp Act, the non-importation movement of 1767–68 mobilized women as political actors.

In 1768, Samuel Adams wrote "The Massachusetts Circular" to the other colonial legislatures, asserting the unconstitutionality of taxation without representation and encouraging protest through boycotting British goods. This letter's humble tone shows the Massachusetts Assembly’s continued deference to parliamentary authority. Even in that hotbed of political protest, it clearly expresses allegiance to Britain and the hope for a restoration of “natural and constitutional rights.”

Britain’s response to this threat of disobedience served only to unite the colonies further. Lord Hillsborough demanded that the Massachusetts colony retract the letter, and warned that any colonial assemblies that endorsed it would be dissolved. This ultimatum pushed the other colonies to Massachusetts’s side. Even the city of Philadelphia, which had originally opposed the Circular, came around. The Daughters of Liberty once again supported the boycott of British goods. Women resumed spinning bees and again found substitutes for British tea and other goods. Many colonial merchants signed non-importation agreements, and the Daughters of Liberty urged colonial women to buy only from those merchants. The Sons of Liberty used newspapers and circulars to call out by name those merchants who refused to sign such agreements, sometimes threatening violence. The 1768–69 boycott turned the purchase of consumer goods into a political act: A person's very clothes indicated whether they "defended liberty" in homespun or protected parliamentary rights in fine British attire.

Citation: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540. LC-USZ62-43568. Text: "The Townshend Acts," OpenStax. https://open stax.org/books/us-history/pages/5-3-the-townshend-acts-and-colonial-protest. © 1999-2019, Rice University, 6100 Main St, MS-375, Houston, TX 77005. All rights reserved. May 17, 2020.

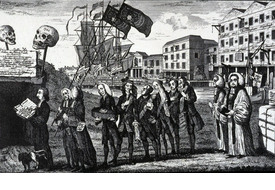

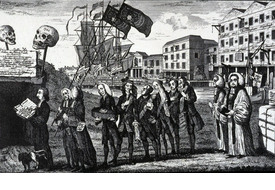

The Repeal, or The Funeral Procession of Miss Americ-Stamp, 1766

Image ID: 7822

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Pre-Revolution, 18th Century Cities, British Empire, Business, Class Separation, Emerging industrial city, Factory as symbol, Imperialism, National Politics, Propaganda, Satire and Comedy, Trade

Region(s): United States, North America

CA Standard(s): 8.1 - Major events preceding the founding of the nation and the development of American constitutional democracy, 5.4 - Political, religious, social, and economic institutions that evolved in the colonial era. , 5.5 - The causes of the American Revolution

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: "The Repeal, or The Funeral Procession of Miss Americ-Stamp," 1766. This cartoon celebrates repeal of the Stamp Act of 1765, depicting its burial at water's edge. The eminent mourners march in a funeral procession toward two skulls on poles in front of trading ships anchored a harbor surrounded by open warehouses full of goods in colonial commerce with America. This cartoon was a most famous and popular political satire commenting on the Stamp Act. Supporters of the act carry a small coffin containing the remains of the bill toward an open vault prepared for the burial of all unjust acts that would alienate Englishmen. Leading the procession and preparing to deliver the funeral eulogy is the Reverend W. Scott, who under the name "Anti-Sejanus," published letters in support of the Stamp Act in London's Public Advertiser. A small dog urinates on his leg. Scott is followed by the mourners: Solicitor General Wedderburn and Attorney General Norton, who are mockingly referred to here as "Two Pillars of the Law." "George Stamp" in the foreground represents Lord George Grenville; he carries "his favourite Childs Coffin, Miss Americ Stamp, who was born in 1763 and died hard in 1766." Following him are Lords Bute, Bedford, and Temple, some of the Englishmen responsible for passing the act. Stamps just returned from America are also stacked on the wharf. Directly behind the bale of stamps stands a crate containing a statue of William Pitt, Grenville's archenemy in the Stamp Act controversy.

The dates on the skulls above the vault refer to the uprisings by the Jacobites, supporters of King James after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The Jacobites still believed that the king's authority came from God, not Parliament. The black flags carried by Wedderburn and Norton contain the numbers 71 and 122, the number of votes against the repeal of the Stamp Act in the Houses of Lords and Commons. The ships in the background are labeled "Conway," "Rockingham," and "Grafton." They represent the Parliamentary leaders responsible for the repeal of the bill, and now stand ready to carry goods to America. By setting the action on an English dock, the artist is able to show the large unshipped cargoes destined for America that accumulated while the act was in force. Attributed to Benjamin Wilson, London, England (March 18, 1766)

Citation: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, British Cartoon Prints Collection, Washington, DC 20540. LC-USZ62-1505. Texts: Colonial Williamsburg: http://www.history.org/history/teaching/tchcrpc1.cfm. Joan D. Dolmetsch, "Rebellion and Reconciliation: Satirical Prints on the Revolution at Williamsburg" (Williamsburg, VA, 1976), pp. 38-9. Copyright Digital History 2019. All rights reserved. May 18, 2020.

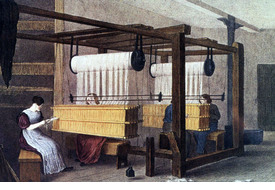

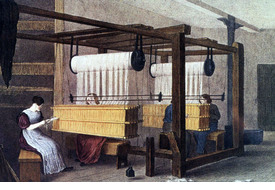

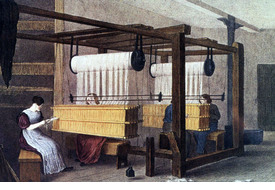

Female and Child Factory Workers Reeding or Drawing in at Loom, England, 1840

Image ID: 8331

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Nineteenth Century, Lowell, Agriculture, Arts and Architecture, British Empire, Business 19th century, Child labor, Class Structure, Cooption of styles, Corporate Image, Early mills and factories, Early National Period, Emerging industrial city, Environmental History, Factory as symbol, Gender-Bending, Imperialism, Industrial Revolution, Institutions and social disorder, Invention, Labor, Labor Organizations and Leaders, Market Economy, National Events, Nineteenth Century Children, Nineteenth Century Furniture, Nineteenth Century Interiors, Strikes and Violence, Success 19th century, Sweatshops, Technology, Urbanization, Victorian Culture, Women and Health, Women in labor movement, Women's organizations, Women's work, Work and Housing, Work and Workers

Region(s): United States, Europe

CA Standard(s): 8.6 - The divergent paths of the American people from 1800 to the mid-1800s...with emphasis on the Northeast. , 5.8 - The colonization, immigration, and settlement patterns of the American people from 1789 to the mid-1800s..., 7.10 - The historical developments of the Scientific Revolution and its lasting effect on religious, political, and cultural institutions, 10.3 - The effects of the Industrial Revolution in England, France, Germany, Japan, and the United States. , 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines

National Standard(s): Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Card Text: Female and child factory workers reeding or drawing in at large cotton loom, England, 1840. Thread reeding is the process of arranging fabric threads on a loom in the correct order before weaving begins. Reeding allows the same loom to make both very fine and very coarse fabric, and to weave threads at very different densities.

"The Beam full of yarn, after being dressed with size to stiffen and strengthen the threads, is brought to the Drawing-in Frame, and hung up as you see in the picture, the Healds which are made of twisted worsted, or Cotton, are hung under the beam and weighted below. The ends of the warp are then drawn down, and the rods hung up to preserve the lease, or the warp could not be woven. There is a female at each side of the healds; one takes hold of the ends of the warp, and gives them separately to the other, who draws them through the healds. When all the ends are through, the Drawing-in is completed. Next comes the Reeding; a reed consists of a great number of short flat pieces of steel or brass called Dents, fixed at short and equal distances from each other, in long pieces of split cane, and tightly secured with a wax band. Through each space, between the dents, two ends are drawn by a small hook, called a Reed-hook. It is not always necessary to draw the warps in; they can also be twisted in, that is, when the warp is nearly all woven into cloth by the weaver, the yarn is cut off, and the fresh warp twisted to the old one. Drawing-in and Reeding is very tedious work and requires great care, there are not only a great number of threads to draw in and reed, but if they were to miss one dent or one heald, it is probable that the whole or a part of the work would have to be done over again. Since this is the case, the steady, careful look of the girls is not to be wondered at."

"Factory Rules from the Handbook to Lowell, 1848: REGULATIONS TO BE OBSERVED by all persons employed in the factories of the Hamilton Manufacturing Company. The overseers are to be always in their rooms at the starting of the mill, and not absent unnecessarily during working hours. They are to see that all those employed in their rooms, are in their places in due season, and keep a correct account of their time and work. They may grant leave of absence to those employed under them, when they have spare hands to supply their places, and not otherwise, except in cases of absolute necessity. All persons in the employ of the Hamilton Manufacturing Company, are to observe the regulations of the room where they are employed. They are not to be absent from their work without the consent of the over-seer, except in cases of sickness, and then they are to send him word of the cause of their absence. They are to board in one of the houses of the company and give information at the counting room, where they board, when they begin, or, whenever they change their boarding place; and are to observe the regulations of their boarding-house. Those intending to leave the employment of the company are to give at least two weeks' notice thereof to their overseer. All persons entering into the employment of the company, are considered as engaged for twelve months, and those who leave sooner, or do not comply with all these regulations, will not be entitled to a regular discharge. The company will not employ anyone who is habitually absent from public worship on the Sabbath, or known to be guilty of immorality. A physician will attend once in every month at the counting-room, to vaccinate all who may need it, free of expense. Anyone who shall take from the mills or the yard, any yarn, cloth or other article belonging to the company, will be considered guilty of stealing and be liable to prosecution. Payment will be made monthly, including board and wages. The accounts will be made up to the last Saturday but one in every month, and paid in the course of the following week. These regulations are considered part of the contract, with which all persons entering into the employment of the Hamilton Manufacturing Company, engage to comply. JOHN AVERY, Agent."

"… Miss Sarah G. Bagl[e]y said she had worked in the Lowell Mills eight years and a half, six years and a half on the Hamilton Corporation, and two years on the Middlesex. She is a weaver, and works by the piece. She worked in the mills three years before her health began to fail. She is a native of New Hampshire, and went home six weeks during the summer. Last year she was out of the mill a third of the time. She thinks the health of the operatives is not so good as the health of females who do housework or millinery business. The chief evil, so far as health is concerned, is the shortness of time allowed for meals. The next evil is the length of time employed - not giving them time to cultivate their minds. She spoke of the high moral and intellectual character of the girls. That many were engaged as teachers in the Sunday schools. That many attended the lectures of the Lowell Institute; and she thought, if more time was allowed, that more lectures would be given and more girls attend. She thought that the girls generally were favorable to the ten hour system. She had presented a petition...to 132 girls, most of whom said that they would prefer to work but ten hours. In a pecuniary point of view, it would be better, as their health would be improved. They would have more time for sewing. Their intellectual, moral and religious habits would also be benefited by the change."

Citation: J.R. Barfoot, "The Progress of Cotton, 1835-40," #9: "Reeding or Drawing in," in a series of 12 prints. Slater Mill Historic Site, 67 Roosevelt Ave, Pawtucket, RI 02860. First text: Public domain: "The Progress of Cotton No. 9: Reading or Drawing In," 1840. From Barfoot's series of colored lithographs of 1840 depicting the cotton manufacturing process. Original text written to accompany Lithograph No.9. https://www.flickr.com/photos/ manchesterarchiveplus/6503188589/in/album-72157629084961692/. Manchester Archives, Manchester Central Library, Manchester City Council, Town Hall, Albert Square, Manchester M60 2LA, UNITED KINGDOM. Second text: Public domain: "Factory Rules from the Handbook to Lowell, 1848." https: //chnm.gmu.edu/mcpstah/wordpress/wp-content/themes/tah/files/mckee_primary-sources.pdf. Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, Department of History and Art History, George Mason University, 4400 University Dr, MSN 1E7, Fairfax, VA 22030. Third text: Public domain.

"Report," Massachusetts House Document, no. 50, March, 1845. https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/bitstream/handle/2452/755732/ocm39986872-1845-HB-0050.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. State Library of Massachusetts, 24 Beacon St, State House Rm 341, Boston, MA 02133. Sept 7, 2023.