Trumbull, The Declaration of Independence, 1786-87

Image ID: 7827

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Eighteenth Century, Pre-Revolution, Politics & Government, 18th Century Interiors, 18th Century Portraits, American Revolution, Ensemble, Founding Myths, Masculinity, National Events, National Politics, Symbols, Upper Class to 1865

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.1 - Major events preceding the founding of the nation and the development of American constitutional democracy, 5.6 - The course and consequences of the American Revolution

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: John Trumbull, "The Declaration of Independence," July 4, 1776, 1818 (placed in the US Capitol Rotunda, Washington, DC, 1826). Like many artists of the early Federal period (c. 1789-1801), Trumbull is little known to most Americans, but many are well aware of his famous paintings. His portrait of Alexander Hamilton, first Secretary of the Treasury, has long graced the ten-dollar bill. Although Trumbull was a portraitist, his ambition lay in painting large historical compositions. This one is most frequently reproduced in history textbooks.

Trumbull was the sixth and youngest child of Jonathan Trumbull and Faith Robinson. If there was an aristocracy in colonial New England, Trumbull was born into it. His Harvard-educated father was a representative to the Connecticut General Assembly, the Governor of Connecticut Colony (1769-76), and after the Revolution, the Governor of the State of Connecticut (1776-84). The artist’s mother was a direct descendant of John Robinson, the so-called “Pastor to the Pilgrim-Fathers” before they sailed on the Mayflower for the New World. Given this prestigious family legacy, Trumbull's father had little interest in allowing his son to pursue a career as a painter. He sent John to Harvard College to find a more useful vocation, in either the law or the ministry. However, in 1772, John visited the artist John Singleton Copley, then still in Boston. Almost half a century later, in 1841, Trumbull still remembered this meeting with great clarity:

"We found Mr. Copley dressed to receive a party of friends at dinner. I remember his dress and appearance—an elegant looking man, dressed in a fine maroon cloth, with gilt buttons—this was dazzling to my unpracticed eye!—but his paintings, the first I had ever seen deserving the name, riveted, absorbed my attention, and renewed all my desire to enter upon such a pursuit." There was no art major at Harvard in the 18th century, so Trumbull studied art in his free time, copying and sketching works that hung on the college’s walls or in its library books. In 1773 he became one of the few artists in early America to complete a college education. Graduating during a tumultuous period, he sought a commission as a Continental Army officer. As a way of introduction, he drew a plan of the British army position at Boston Neck for General Washington. Soon, Washington appointed him as an aide-de-camp (assistant to a senior officer). In 1776, Major General Horatio Gates appointed Trumbull deputy adjutant-general (military chief administrative officer) at the rank of Colonel, a title he carried for the rest of his life.

Because of his military experience, Trumbull believed that he was uniquely qualified to depict the major events of the American Revolutionary War. His first step was to get artistic training, and in 1780 sailed for London and the studio of Benjamin West, an American artist with a successful career in England. Trumbull was decidedly anti-British, and in November 1780 he was arrested and charged with treason. He was imprisoned for more than 8 months and released only after powerful friends, like West and the statesman Edmund Burke, appealed to the Privy Council. Trumbull was given 30 days to leave Great Britain.

Trumbull returned to Connecticut for two years, where his father again tried to convince him to pursue a more profitable vocation. Undeterred, Trumbull returned to West’s studio in London in 1784, where he made quick progress. Growing in confidence, he was determined to return to the newly formed United States with paintings commemorating its recent victory over Great Britain. Writing to his father in 1785, Trumbull explained, "The great object of my wishes...is to take up the History of Our Country, and paint the principal Events" of that late war. By the end of the year he had already begun work on "The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker's Hill," and "The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec." In 1786 Trumbull began to plan three other Revolutionary War paintings: "The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton," "The Capture of Hessians at Trenton," and "The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown." That summer he accepted Thomas Jefferson's invitation to visit Paris, where he began the sketches for this painting, "The Declaration of Independence." He incorporated Jefferson's memory of the events in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia, where the Declaration was first presented to Congress and later signed. This painting, resulting from this collaboration between artist and politician, has become one of the most famous images in the history of American art.

The so-called Committee of Five was primarily responsible for the written document. They are, from left to right: John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Robert R. Livingston of New York, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, and Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania. Jefferson presents the document to John Hancock, the President of the Continental Congress. Oil on canvas. 20-7/8 x 31."

Citation: John Trumbull, "The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776," 1786–1820. Yale University Art Gallery, 1111 Chapel St, New Haven, CT 06510. Image: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Horydczak Collection, Washington, DC 20540. LC-H8-CT-C01-062-A. Text: Dr. Bryan Zygmont, "John Trumbull, The Declaration of Independence." Copyright Smarthistory, Feb 25, 2016. https://smarthistory.org/trumbull-declaration/. All rights reserved. May 19, 2020.

'Apotheosis of George Washington'

Image ID: 4595

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): National Politics, Early National Period, Politics & Government

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.4 - The aspirations and ideals of the people of the new nation

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: "Apotheosis of George Washington," 19th century, watercolor on glass.

Citation: Copyright holder unknown. Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, DE 19735. Morristown National Historical Park, MORR 941. In Francis Russell and the Eds. of American Heritage, The American Heritage History of the Making of the Nation, 1783-1860, 1968, p. 66.

8.4.2

Elven, George Washington Giving the Laws, c. 1800

Image ID: 7913

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Eighteenth Century, Washington, Politics & Government, American Revolution, Ancient History, Art Style, Columbian Exchange, Cooption of styles, Early National Period, Founding Myths, Greece Ancient, Holy Land, Mythology, National Events, Numinous, Personalization, Presidents, Propaganda, Religion, Roman, Symbols, Women's image

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.6 - The divergent paths of the American people from 1800 to the mid-1800s...with emphasis on the Northeast. , 8.1 - Major events preceding the founding of the nation and the development of American constitutional democracy, 5.6 - The course and consequences of the American Revolution, 5.7 - People and events associated with the development of the U.S. Constitution and it's significance as the foundation of the American republic

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: J.P. Elven, "Washington Giving the Laws to America," c. 1800. The deification of George Washington. An elderly man wearing a Roman toga, representing Washington, holds a stone tablet entitled "The American Constitution." He is surrounded by allegorical figures. Britannia and her lion sit at his feet while female figures symbolizing government, industry and the arts move in the background. The Greek gods Athena (Minerva) and Hermes (Mercury) are placed before a temple in the right background, as the archangel Gabriel, flying above the scene, blows his trumpet and carries a shield emblazoned with the American emblem.

At the time this work was created, important figures were commonly shown in allegorical settings. Greece and Rome had melded to symbolize a Golden Age of humankind. Competent artists were well versed in the ancients and mythology, and this engraving depicts Washington as a Roman, a symbol of a new age of republican leadership and the struggle for independence. Dressing a people's president as an emperor or tyrant personified to the revolutionary mind the heroic, noble ancient world, not the literal one.

In classical garb, Washington holds a stylus and a slab engraved "The American Constitution." He is flanked by Justice, who holds the fasces, a bundle of rods with a projecting axe blade, the Roman symbol of authority and the power of the law; and by Truth, holding her familiar mirror. Liberty was often shown as attended by Peace, Justice, and Truth.

At Washington's right, Liberty restrains a lion, the symbol of the British Empire, the oppressor defeated by Washington: She also holds back any attempt by the new nation to build an empire of its own. Above Washington, the angel Gabriel symbolizes God's power and judgment, sounding the call of freedom represented by the American coat of arms.

A body of water separates Washington from a group of figures at right including Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and war, wearing armor and carrying a shield and spear. With her are two female figures, one holding a palette and brushes representing the arts. Above them in a bank of clouds is Mercury, the Roman god of commerce and messenger of the gods. The Romans historically offered the first fruit of a tree to Mercury, asking his blessing on any new enterprise. Mercury points toward the temple rising behind him, a symbol of the Kingdom of God. In the foreground a well-muscled Hercules in an animal skin and a crown of laurel reclines in his godly strength. Engraving and etching. 15 x 7 cm.

Citation: "Washington Giving the Laws to America," United States, c. 1800. Photograph and first text: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540. LC-DIG-ds-05302. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014645020/. Second text: "An Important Recently Discovered Tribute to George Washington and America, 'George Washington Giving the Laws to America,' New England. Anonymous, c. 1800." Copyright 2003-19 Antique Associates, 73 Main St, PO Box 129W, West Townsend, MA 01474. https://www.aaawt.com/html/sold/136.html. All rights reserved. Oct 22, 2021.

George Caleb Bingham, 'Stump Speaking' 1853-54

Image ID: 8667

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Nineteenth Century, Genre Painting, Politics & Government

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.2 - The political principles underlying the U.S. Constitution and compare the enumerated and implied powers of the federal government

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: George Caleb Bingham, "Stump Speaking," 1853-54, detail, oil on canvas, 108 x 147.3 cm.

Citation: Courtesy of The St. Louis Art Museum, 1 Fine Arts Dr, Forest Park, St. Louis, MO 63110. All rights reserved. We are grateful for the generosity of the St. Louis Art Museum.

George Caleb Bingham, 'The Verdict of the People' 1854-5

Image ID: 8737

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Nineteenth Century, Working Class Culture, Politics & Government

Region(s): South America

CA Standard(s): 8.2 - The political principles underlying the U.S. Constitution and compare the enumerated and implied powers of the federal government

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: George Caleb Bingham, "The Verdict of the People," 1854-5, oil on canvas, 42 ½ x 58 in.

Citation: Courtesy of The St. Louis Art Museum, 1 Fine Arts Dr, St. Louis, MO 63110. All rights reserved. Our thanks to the Museum.

A. Wighe, 'Trial by Jury' 1849

Image ID: 11341

Collection: Louis Warren

Topic(s): Politics & Government

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.2 - The political principles underlying the U.S. Constitution and compare the enumerated and implied powers of the federal government

National Standard(s): Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Card Text: Courtroom scene of early America, 1849, an informal, "frolicking time." A. Wighe, "Trial by Jury," painting.

Citation: ASK Copyright © Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, 224 Benefit St, Providence, RI 02903. Gift of Edith Jackson Green and Ellis Jackson. All rights reserved.

Theophilus Adam Wylie, 'Political Scene [Meeting] in Early Bloomington' 1837

Image ID: 4065

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): Social Disorder, Social disorder and order to 1865, Politics & Government

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.3 - The foundation of the American political system and the ways in which citizens participate in it

National Standard(s): Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Card Text: Theophilus Adam Wylie, "Political Scene [Meeting] in Early Bloomington," 1837.

Citation: Copyright holder and location unknown. Indiana University?

8.3.1

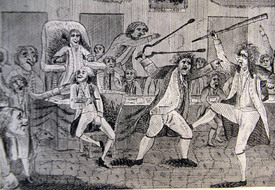

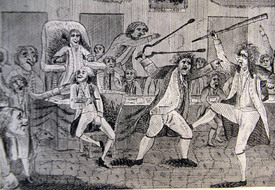

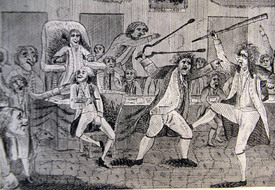

Cartoon: 'Congressional pugilists' 1798

Image ID: 11739

Collection: Louis Warren

Topic(s): Politics & Government

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.2 - The political principles underlying the U.S. Constitution and compare the enumerated and implied powers of the federal government, 8.3 - The foundation of the American political system and the ways in which citizens participate in it

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: "Congressional pugilists," a heated partisan debate, cartoon, 1798. A fight on the floor of Congress between Vermont Representative Matthew Lyon, a Jeffersonian Republican, and Roger Griswold of Connecticut, a Federalist. "Griswold had accused Lyon of cowardice during the American Revolution and Lyon responded by spitting tobacco juice in Griswold's face." The interior of Congress Hall is shown. Several others look on as Griswold, armed with a cane, kicks Lyon, who grasps his arm and raises a pair of fireplace tongs to strike him. Below are the verses: "He in a trice struck Lyon thrice / Upon his head, enrag'd sir, / Who seiz'd the tongs to ease his wrongs, / And Griswold thus engag'd, sir." Print, 1798, Philadelphia.

Citation: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540. LC-DIG-ppmsca-15707.

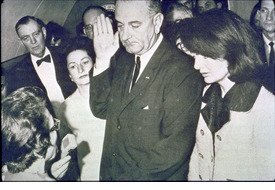

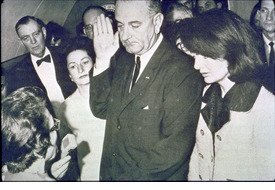

Photo: Lyndon Johnson taking the oath of office

Image ID: 4339

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): National Politics, Kennedy, Politics & Government

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.11 - Major social problems and domestic policy issues in contemporary American society

National Standard(s): Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Card Text: Lyndon Johnson taking the oath of office in the airplane, flanked by Lady Bird and Jacqueline Kennedy. The swearing in was performed by Federal District Judge Sarah T. Hughes of Dallas. Johnson was President of the U.S. when he landed in the capital.

Citation: Cecil Stoughton photo. Courtesy Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum, 2313 Red River St., Austin, TX 78705. 1A-1-WH63. In Paul K. Conkin & David Burner, A History of Recent America, 1974, p. 569.

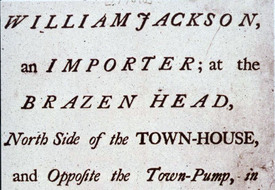

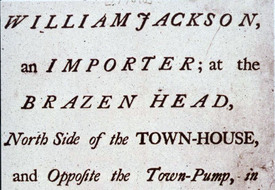

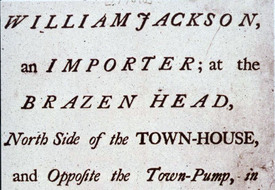

Broadside, Boycott of Merchant who Continued to Stock English Goods, Boston, 1770

Image ID: 7820

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Eighteenth Century, Revolution, American Revolution, British Empire, Business, Civil Rights, Class Structure, Colonial America, Decolonization, Domesticity, Early Ads, Imperialism, Individualism, Technology, Institutions and social disorder, Invention, Labor Organizations and Leaders, Luxury, Middle-Class Culture, National Events, Nativism, Politics & Government, Pre-Industrial Work - Misc., Propaganda, Stores, Strikes and Violence, Symbols, Taxes, Trade, Women in the Revolution, Women's image, Women's organizations, Work and Workers

Region(s): United States, North America

CA Standard(s): 8.1 - Major events preceding the founding of the nation and the development of American constitutional democracy, 5.4 - Political, religious, social, and economic institutions that evolved in the colonial era. , 5.5 - The causes of the American Revolution, 5.6 - The course and consequences of the American Revolution, 5.7 - People and events associated with the development of the U.S. Constitution and it's significance as the foundation of the American republic

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: Broadside urging the American boycott of merchant William Jackson, who continued to stock English goods at his Boston business, MA, 1770. "It is desired that the Sons and Daughters of Liberty, would not buy any one thing of him, for in so doing they will bring disgrace upon themselves, and their Posterity, for ever and ever, AMEN." Like the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767 produced controversy and protest in the American colonies. Many colonists again resented an effort to tax them without representation and thus to deprive them of their liberty. The revenue raised by the Townshend Acts would pay royal governors, taking away the right of colonial legislatures to set or withhold a royal governor’s salary. The Restraining Act, intended to isolate New York without angering the other colonies, had the opposite effect, showing how far beyond the British Constitution some members of Parliament were willing to go.

The Townshend Acts generated a number of protest writings, including “Letters from a Pennsylvania Farmer” by John Dickinson. This influential pamphlet circulated widely in the colonies, arguing that Parliament could not impose either internal taxes, like stamps on goods, or external taxes, like customs duties on imports.

Women were encouraged to boycott British goods, especially tea and linen, and to manufacture their own homespun cloth. Building on the Daughters of Liberty protest of the 1765 Stamp Act, the non-importation movement of 1767–68 mobilized women as political actors.

In 1768, Samuel Adams wrote "The Massachusetts Circular" to the other colonial legislatures, asserting the unconstitutionality of taxation without representation and encouraging protest through boycotting British goods. This letter's humble tone shows the Massachusetts Assembly’s continued deference to parliamentary authority. Even in that hotbed of political protest, it clearly expresses allegiance to Britain and the hope for a restoration of “natural and constitutional rights.”

Britain’s response to this threat of disobedience served only to unite the colonies further. Lord Hillsborough demanded that the Massachusetts colony retract the letter, and warned that any colonial assemblies that endorsed it would be dissolved. This ultimatum pushed the other colonies to Massachusetts’s side. Even the city of Philadelphia, which had originally opposed the Circular, came around. The Daughters of Liberty once again supported the boycott of British goods. Women resumed spinning bees and again found substitutes for British tea and other goods. Many colonial merchants signed non-importation agreements, and the Daughters of Liberty urged colonial women to buy only from those merchants. The Sons of Liberty used newspapers and circulars to call out by name those merchants who refused to sign such agreements, sometimes threatening violence. The 1768–69 boycott turned the purchase of consumer goods into a political act: A person's very clothes indicated whether they "defended liberty" in homespun or protected parliamentary rights in fine British attire.

Citation: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540. LC-USZ62-43568. Text: "The Townshend Acts," OpenStax. https://open stax.org/books/us-history/pages/5-3-the-townshend-acts-and-colonial-protest. © 1999-2019, Rice University, 6100 Main St, MS-375, Houston, TX 77005. All rights reserved. May 17, 2020.