Poster: 'To Protect Our Way of Living'

Image ID: 2605

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): War Posters, W.W.II, Propaganda

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.7 - America's participation in World War II

National Standard(s): The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Card Text: Poster, "To Protect Our Way of Living." A blond couple walk hand in hand on top of a hill, with planes overhead and factories pumping out white smoke behind them. World War II.

Citation: U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. Quantity Postcards, 1441 Grant Ave., San Francisco, CA.

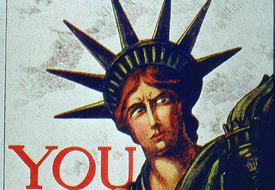

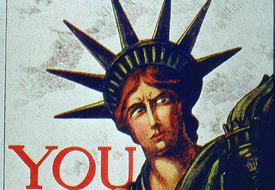

Poster: 'YOU buy a LIBERTY BOND…LEST I PERISH'

Image ID: 3716

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): Symbols, Statue of Liberty, Propaganda

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.4 - The rise of the United States to its role as a world power in the twentieth century

National Standard(s): The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Card Text: "YOU buy a LIBERTY BOND…LEST I PERISH." Poster. The Statue of Liberty points a finger in James Montgomery Flagg style. Not until the outbreak of World War I did the Statue of Liberty become a national and international symbol of freedom and peace.

Citation: The New-York Historical Society, 170 Central Park West, New York, NY 10024. In James B. Bell and Richard Abrams, "In Search of Liberty," 1984, p. 61.

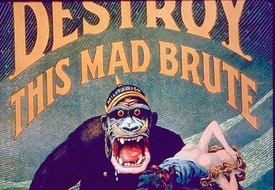

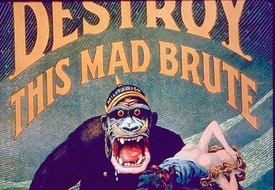

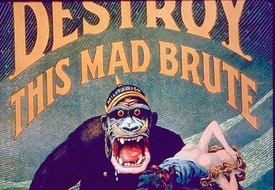

Poster: 'Destroy This Mad Brute' 1917

Image ID: 2652

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): War Posters, W.W.I, Propaganda

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.4 - The rise of the United States to its role as a world power in the twentieth century

National Standard(s): The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Card Text: Poster, "Destroy This Mad Brute...ENLIST if you want to fight for your country...If this war is not fought to a finish in Europe, it will be on the soil of the United States," 1917. Ad, U.S. Army, World War I. Kaiser Wilhelm II has been turned into a huge, black, insane ape wearing a German spiked helmet labeled "Militarism," abducting a terrified Columbia for rape, bringing down a bloodied club labelled "KULTUR" on "AMERICA," and threatening the next victim, the viewer. Blood drenches his hands and wrists. This slobbering beast personifies several other stereotypes, racial ones included. H.R. Hopps poster.

Citation: Army Recruiting Station, Boston, MA. Hoover Institution Archives, Poster Collection, US 2003A, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-6010.

11.4.5

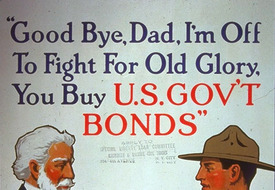

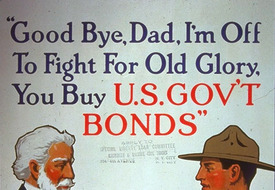

Poster: 'Good Bye, Dad. I'm Off to Fight for Old Glory' 1918

Image ID: 2664

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): War Posters, W.W.I, Propaganda

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.4 - The rise of the United States to its role as a world power in the twentieth century

National Standard(s): The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Card Text: Poster, "Good Bye, Dad. I'm Off to Fight for Old Glory, You Buy U.S. Gov't Bonds...Third Liberty Loan," 1918. A young soldier shakes hands with his white-haired, white-bearded father; in the background are a few houses in rolling countryside. Rural imagery. Laurence S. Harris.

Citation: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540. LC-USZ62-42152.

West Africans Examine British Armed Forces Ad, World War II

Image ID: 13469

Collection: Cynthia Brantley

Topic(s): W.W.II, Imperialism, Propaganda, War Posters

Region(s): Africa, Europe

CA Standard(s): 10.4 - Global change in the era of New Imperialism in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, India, Latin America, and the Philippines, 10.8 - The causes and consequences of World War II

National Standard(s): A Half-Century of Crisis and Achievement, 1900-1945

Card Text: "Together." Young West Africans looking at a World War II advertisement for the armed forces of the British Commonwealth, c. 1940. One man points at the African member of the "team." British war propaganda tried to convey an image of unity among the colonies that was not so apparent in real life. "For King and country. As happened throughout the Empire during the Second World War, men of military age were called up for service in their countries' armed forces. Recruiting propaganda stressed the unity of the British Commonwealth of Nations, a point being reinforced to these young men who are about to join the Royal West African Frontier Force." The RWAFF served as a cadre for the formation of two West African divisions, which fought in Italian Somaliland, Abyssinia (Ethiopia), and Burma. One of several ads produced with similar graphics and the same message.

Citation: Imperial War Museum, Lambeth Rd, London SE1 6HZ UNITED KINGDOM. Online at www.iwm.org.uk. In Trevor Royle, "Winds of Change: The End of Empire in Africa," (John Murray Ltd, 50 Albemarle St, London W1X 4BD UNITED KINGDOM, 1997) Fig. 1, opp. p. 116.

Poster: 'Longing won't get him back sooner... GET A WAR JOB!' 1944

Image ID: 2589

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): War Posters, W.W.II, World War II, Propaganda, Women in war

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.7 - America's participation in World War II

National Standard(s): The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Card Text: Poster, "Longing won't get him back sooner... GET A WAR JOB! See Your U.S. Employment Service," 1944. World War II. Lawrence Wilbur.

Citation: War Manpower Commission. US National Archives and Records Administration, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001.

Proslavery propaganda, 1852

Image ID: 8894

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Nineteenth Century, Nineteenth Century Slavery, Slavery and Abolition, Propaganda

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.7 - The divergent paths of the American people in the South from 1800 to the mid-1800s

National Standard(s): Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877) , Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Card Text: Proslavery propaganda: "The Negro In His Own Country" vs. "The Negro In America," from "Bible Defence of Slavery," 1852

Citation: Josiah Priest, "Bible Defence of Slavery," W. S. Brown: Glasgow, KY 1852. Chicago Historical Society, 1601 N Clark St, Chicago, IL 60614

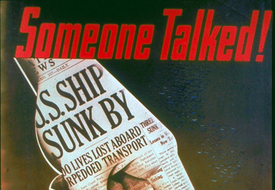

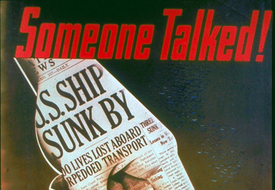

Poster: 'Someone Talked!' 1943

Image ID: 2645

Collection: Roland Marchand

Topic(s): War Posters, W.W.II, Propaganda

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 11.7 - America's participation in World War II

National Standard(s): The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Card Text: Poster, "Someone Talked!" 1943. Office of War Information. Henry Koerner.

Citation: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540. LC-USZC4-1858.

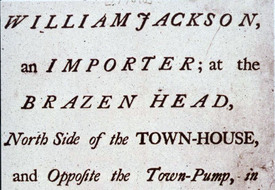

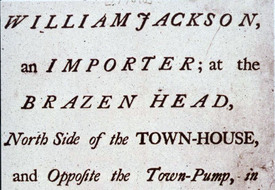

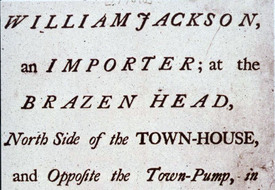

Broadside, Boycott of Merchant who Continued to Stock English Goods, Boston, 1770

Image ID: 7820

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Eighteenth Century, Revolution, American Revolution, British Empire, Business, Civil Rights, Class Structure, Colonial America, Decolonization, Domesticity, Early Ads, Imperialism, Individualism, Technology, Institutions and social disorder, Invention, Labor Organizations and Leaders, Luxury, Middle-Class Culture, National Events, Nativism, Politics & Government, Pre-Industrial Work - Misc., Propaganda, Stores, Strikes and Violence, Symbols, Taxes, Trade, Women in the Revolution, Women's image, Women's organizations, Work and Workers

Region(s): United States, North America

CA Standard(s): 8.1 - Major events preceding the founding of the nation and the development of American constitutional democracy, 5.4 - Political, religious, social, and economic institutions that evolved in the colonial era. , 5.5 - The causes of the American Revolution, 5.6 - The course and consequences of the American Revolution, 5.7 - People and events associated with the development of the U.S. Constitution and it's significance as the foundation of the American republic

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: Broadside urging the American boycott of merchant William Jackson, who continued to stock English goods at his Boston business, MA, 1770. "It is desired that the Sons and Daughters of Liberty, would not buy any one thing of him, for in so doing they will bring disgrace upon themselves, and their Posterity, for ever and ever, AMEN." Like the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767 produced controversy and protest in the American colonies. Many colonists again resented an effort to tax them without representation and thus to deprive them of their liberty. The revenue raised by the Townshend Acts would pay royal governors, taking away the right of colonial legislatures to set or withhold a royal governor’s salary. The Restraining Act, intended to isolate New York without angering the other colonies, had the opposite effect, showing how far beyond the British Constitution some members of Parliament were willing to go.

The Townshend Acts generated a number of protest writings, including “Letters from a Pennsylvania Farmer” by John Dickinson. This influential pamphlet circulated widely in the colonies, arguing that Parliament could not impose either internal taxes, like stamps on goods, or external taxes, like customs duties on imports.

Women were encouraged to boycott British goods, especially tea and linen, and to manufacture their own homespun cloth. Building on the Daughters of Liberty protest of the 1765 Stamp Act, the non-importation movement of 1767–68 mobilized women as political actors.

In 1768, Samuel Adams wrote "The Massachusetts Circular" to the other colonial legislatures, asserting the unconstitutionality of taxation without representation and encouraging protest through boycotting British goods. This letter's humble tone shows the Massachusetts Assembly’s continued deference to parliamentary authority. Even in that hotbed of political protest, it clearly expresses allegiance to Britain and the hope for a restoration of “natural and constitutional rights.”

Britain’s response to this threat of disobedience served only to unite the colonies further. Lord Hillsborough demanded that the Massachusetts colony retract the letter, and warned that any colonial assemblies that endorsed it would be dissolved. This ultimatum pushed the other colonies to Massachusetts’s side. Even the city of Philadelphia, which had originally opposed the Circular, came around. The Daughters of Liberty once again supported the boycott of British goods. Women resumed spinning bees and again found substitutes for British tea and other goods. Many colonial merchants signed non-importation agreements, and the Daughters of Liberty urged colonial women to buy only from those merchants. The Sons of Liberty used newspapers and circulars to call out by name those merchants who refused to sign such agreements, sometimes threatening violence. The 1768–69 boycott turned the purchase of consumer goods into a political act: A person's very clothes indicated whether they "defended liberty" in homespun or protected parliamentary rights in fine British attire.

Citation: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540. LC-USZ62-43568. Text: "The Townshend Acts," OpenStax. https://open stax.org/books/us-history/pages/5-3-the-townshend-acts-and-colonial-protest. © 1999-2019, Rice University, 6100 Main St, MS-375, Houston, TX 77005. All rights reserved. May 17, 2020.

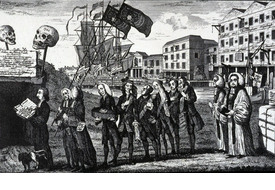

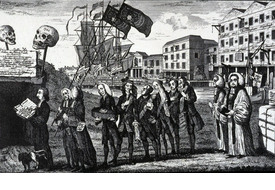

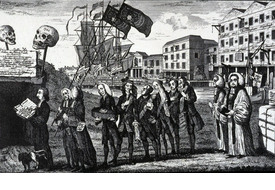

The Repeal, or The Funeral Procession of Miss Americ-Stamp, 1766

Image ID: 7822

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Pre-Revolution, 18th Century Cities, British Empire, Business, Class Separation, Emerging industrial city, Factory as symbol, Imperialism, National Politics, Propaganda, Satire and Comedy, Trade

Region(s): United States, North America

CA Standard(s): 8.1 - Major events preceding the founding of the nation and the development of American constitutional democracy, 5.4 - Political, religious, social, and economic institutions that evolved in the colonial era. , 5.5 - The causes of the American Revolution

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: "The Repeal, or The Funeral Procession of Miss Americ-Stamp," 1766. This cartoon celebrates repeal of the Stamp Act of 1765, depicting its burial at water's edge. The eminent mourners march in a funeral procession toward two skulls on poles in front of trading ships anchored a harbor surrounded by open warehouses full of goods in colonial commerce with America. This cartoon was a most famous and popular political satire commenting on the Stamp Act. Supporters of the act carry a small coffin containing the remains of the bill toward an open vault prepared for the burial of all unjust acts that would alienate Englishmen. Leading the procession and preparing to deliver the funeral eulogy is the Reverend W. Scott, who under the name "Anti-Sejanus," published letters in support of the Stamp Act in London's Public Advertiser. A small dog urinates on his leg. Scott is followed by the mourners: Solicitor General Wedderburn and Attorney General Norton, who are mockingly referred to here as "Two Pillars of the Law." "George Stamp" in the foreground represents Lord George Grenville; he carries "his favourite Childs Coffin, Miss Americ Stamp, who was born in 1763 and died hard in 1766." Following him are Lords Bute, Bedford, and Temple, some of the Englishmen responsible for passing the act. Stamps just returned from America are also stacked on the wharf. Directly behind the bale of stamps stands a crate containing a statue of William Pitt, Grenville's archenemy in the Stamp Act controversy.

The dates on the skulls above the vault refer to the uprisings by the Jacobites, supporters of King James after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The Jacobites still believed that the king's authority came from God, not Parliament. The black flags carried by Wedderburn and Norton contain the numbers 71 and 122, the number of votes against the repeal of the Stamp Act in the Houses of Lords and Commons. The ships in the background are labeled "Conway," "Rockingham," and "Grafton." They represent the Parliamentary leaders responsible for the repeal of the bill, and now stand ready to carry goods to America. By setting the action on an English dock, the artist is able to show the large unshipped cargoes destined for America that accumulated while the act was in force. Attributed to Benjamin Wilson, London, England (March 18, 1766)

Citation: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, British Cartoon Prints Collection, Washington, DC 20540. LC-USZ62-1505. Texts: Colonial Williamsburg: http://www.history.org/history/teaching/tchcrpc1.cfm. Joan D. Dolmetsch, "Rebellion and Reconciliation: Satirical Prints on the Revolution at Williamsburg" (Williamsburg, VA, 1976), pp. 38-9. Copyright Digital History 2019. All rights reserved. May 18, 2020.

Elven, George Washington Giving the Laws, c. 1800

Image ID: 7913

Collection: Karen Halttunen

Topic(s): Eighteenth Century, Washington, Politics & Government, American Revolution, Ancient History, Art Style, Columbian Exchange, Cooption of styles, Early National Period, Founding Myths, Greece Ancient, Holy Land, Mythology, National Events, Numinous, Personalization, Presidents, Propaganda, Religion, Roman, Symbols, Women's image

Region(s): United States

CA Standard(s): 8.6 - The divergent paths of the American people from 1800 to the mid-1800s...with emphasis on the Northeast. , 8.1 - Major events preceding the founding of the nation and the development of American constitutional democracy, 5.6 - The course and consequences of the American Revolution, 5.7 - People and events associated with the development of the U.S. Constitution and it's significance as the foundation of the American republic

National Standard(s): Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Card Text: J.P. Elven, "Washington Giving the Laws to America," c. 1800. The deification of George Washington. An elderly man wearing a Roman toga, representing Washington, holds a stone tablet entitled "The American Constitution." He is surrounded by allegorical figures. Britannia and her lion sit at his feet while female figures symbolizing government, industry and the arts move in the background. The Greek gods Athena (Minerva) and Hermes (Mercury) are placed before a temple in the right background, as the archangel Gabriel, flying above the scene, blows his trumpet and carries a shield emblazoned with the American emblem.

At the time this work was created, important figures were commonly shown in allegorical settings. Greece and Rome had melded to symbolize a Golden Age of humankind. Competent artists were well versed in the ancients and mythology, and this engraving depicts Washington as a Roman, a symbol of a new age of republican leadership and the struggle for independence. Dressing a people's president as an emperor or tyrant personified to the revolutionary mind the heroic, noble ancient world, not the literal one.

In classical garb, Washington holds a stylus and a slab engraved "The American Constitution." He is flanked by Justice, who holds the fasces, a bundle of rods with a projecting axe blade, the Roman symbol of authority and the power of the law; and by Truth, holding her familiar mirror. Liberty was often shown as attended by Peace, Justice, and Truth.

At Washington's right, Liberty restrains a lion, the symbol of the British Empire, the oppressor defeated by Washington: She also holds back any attempt by the new nation to build an empire of its own. Above Washington, the angel Gabriel symbolizes God's power and judgment, sounding the call of freedom represented by the American coat of arms.

A body of water separates Washington from a group of figures at right including Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and war, wearing armor and carrying a shield and spear. With her are two female figures, one holding a palette and brushes representing the arts. Above them in a bank of clouds is Mercury, the Roman god of commerce and messenger of the gods. The Romans historically offered the first fruit of a tree to Mercury, asking his blessing on any new enterprise. Mercury points toward the temple rising behind him, a symbol of the Kingdom of God. In the foreground a well-muscled Hercules in an animal skin and a crown of laurel reclines in his godly strength. Engraving and etching. 15 x 7 cm.

Citation: "Washington Giving the Laws to America," United States, c. 1800. Photograph and first text: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC 20540. LC-DIG-ds-05302. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014645020/. Second text: "An Important Recently Discovered Tribute to George Washington and America, 'George Washington Giving the Laws to America,' New England. Anonymous, c. 1800." Copyright 2003-19 Antique Associates, 73 Main St, PO Box 129W, West Townsend, MA 01474. https://www.aaawt.com/html/sold/136.html. All rights reserved. Oct 22, 2021.